Participation up in second Puget Sound ship slowdown to protect endangered orcas

After a successful trial, Quiet Sound marked several new milestones in the 2023-2024 slowdown

It gets frustrating, even stressful, trying to communicate with someone in a loud venue like a concert, near a barking dog, or even a house packed with family members.

Imagine being able to summon a dial and turn the volume down, reducing that background noise by 45%.

That’s the impact that Quiet Sound reported from its voluntary ship slowdown trial, which ran from October 2022 to January 2023. Instead of an imaginary dial, the Washington Maritime Blue program targeted the small group of large vessels that generate over 80% of vessel-related underwater noise.

And instead of trying to preserve your sanity with less noise, Quiet Sound is focused on reducing the impacts of underwater noise – which has grown exponentially since the 1960s – for Southern Resident killer whales (SRKW).

Southern Resident killer whales are...

- Different from transient or Bigg’s killer whales, which also spend time in Puget Sound.

- Dependent on fish, primarily Chinook salmon, for their diet.

- Protected by law, including one requiring vessels to stay at least 300-400 yards (increasing to 1,000 yards in 2025) away from the whales.

These endangered orcas are iconic in the Pacific Northwest and for almost half a century, their population has numbered less than 100. Excess underwater noise impacts their acoustic communication and is one of three main issues NOAA contributes to the SRKW’s decline.

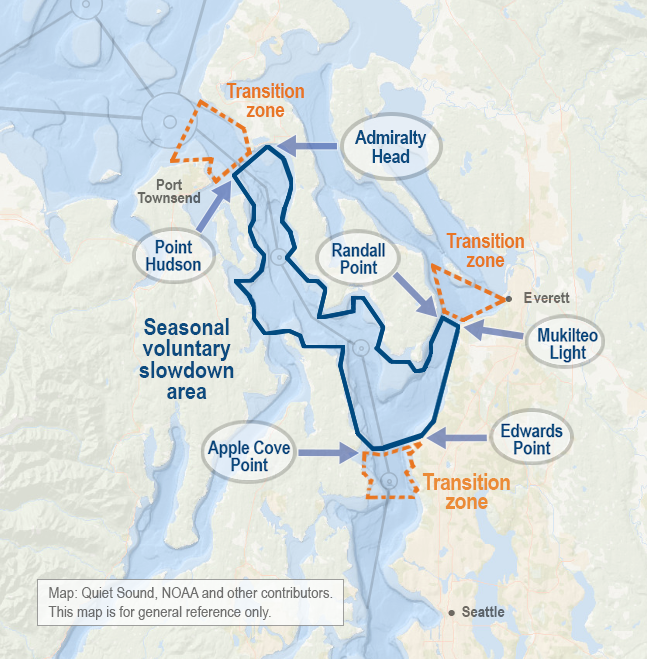

Last year, on October 12, the whales entered Admiralty Inlet triggering the second voluntary slowdown. It was time for Quiet Sound to get the word out and put into practice what they learned from the previous year's trial.

The 2023-2024 voluntary slowdown

Rachel Aronson, the Quiet Sound program director, said they decided to repeat the slowdown because there wasn’t any impact to maritime safety and industry. In an interview soon after the second slowdown started, she said they were focused on a few key changes for round two.

First, to try and be sure this sound intervention occurred at the right time, they tied the start of the slowdown to when the Southern Resident orcas first entered the slowdown area after October 1.

Another change is ongoing research to measure vessel speeds. According to Aronson, a vessel’s speed through the water, instead of its speed over ground, is more accurate for quantifying the acoustic impacts of that vessel. But the local tides and currents in Puget Sound complicate things.

Using AIS data, Quiet Sound is testing different tidal models to see which most accurately reflects the speeds reported after each voyage by Puget Sound Pilots, a key program partner.

Tankers, container ships, cruise ships and other large vessels all have a local pilot on board when arriving or departing from the ports along Puget Sound. They bring local knowledge and perspective, including about Quiet Sound.

These pilots are “the humans on board representing the slowdown,” Aronson said. “[We] so appreciate their leadership on this conservation initiative.”

Asked why a vessel might not choose to participate, Aronson said it might be due to the pressures of their schedule or weather. The slowdown period takes place during a choppy, windy time of year.

The voluntary nature of the slowdown gives pilots and captains flexibility to do what’s safest, a perennial concern on the water. Quiet Sound was also an unknown entity during the initial trial. Now, awareness has increased.

Aronson said they believe ongoing communication is key. When participation trailed off during the trial, they sent out a bunch of emails and participation bounced back. Sustaining that communication and awareness became a focus for the second slowdown.

The science of less sound

Gathering and assessing acoustic data is another key part of the program. The findings from the trial were motivating for the coalition of partners that Quiet Sound brings together.

For the 2022-2023 trial, Quiet Sound gathered baseline data and reported four key metrics:

- 70% of vessels transiting through the slowdown area reduced speed.

- 53% of the transits reached the speed targets. (11 knots or 14.5 knots, depending on vessel type. That's about 12-16 mph.)

- There was a 45% reduction in sound intensity. (That magic dial!)

- And SRKW were present in the area for 45% of the slowdown period.

By monitoring a hydrophone in Useless Bay off Whidbey Island, marine mammal researchers found “median broadband sound levels were reduced by 2.8 decibels.” But what does that mean?

“We made it quieter on all the frequencies that we can measure sound, including the frequencies that orcas use,” Aronson explained.

She said they are very motivated to continue improving Quiet Sound’s current programs, and making sure the science and data support that work.

How slow did they go?

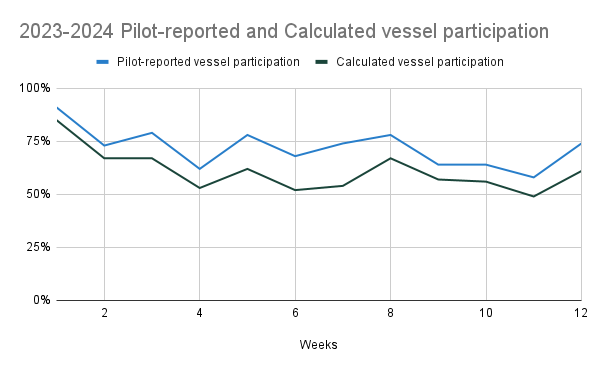

Quiet Sound closely tracks two metrics each week for participation. One is based on reports from the Puget Sound Pilots and the other uses AIS data from Marine Exchange of Puget Sound with one of the tidal models.

Vessels are considered participating if they slow down, even without hitting the target speeds. Quiet Sound encourages any reduction in speed.

The second slowdown started strong with pilots reporting participation over 90% the first week. Cruise ships also participated for the first time, since the whale-triggered slowdown began a few weeks before the end of the cruise season.

At the 12 week mark, container ships had one of the highest participation rates at 68%, they also account for the highest number of transits. Passenger vessels, including cruise ships, had an 85% participation rate, but a lot fewer transits since they only overlapped with the slowdown period for four weeks.

Preliminary data shared by Quiet Sound after the slowdown officially ended January 12 shows that overall, participation increased:

- 72% of vessels slowed their speed while transiting through the slowdown area — up 2% from the trial.

- 59% of vessels fully met the proposed speed targets — up 6% from the trial.

The slowdown's impact on sound intensity and how often SRKW were in the area are expected in the final report, coming later this year.

Thanks, Canada

While a voluntary vessel slowdown is relatively new to Washington, they exist elsewhere on the West Coast, including British Columbia. The East Coast has a mix of mandatory and voluntary slowdown areas.

Quiet Sound has benefited from studying existing slowdowns, in particular a program launched by the Port of Vancouver in 2017. The Enhancing Cetacean Habitat and Observation (ECHO) Program includes three initiatives geared towards reducing underwater noise for the same group of endangered orcas.

While both Quiet Sound and the ECHO program are focused on acoustic reductions, the Port of Vancouver reports its initiatives also reduce emissions by 17%, and lower the risk of whale strikes.

Aronson said without the ECHO program, Quiet Sound would not be where they are after only two years.

What's next for Quiet Sound

Early on in the slowdown, Aronson said she’d be thrilled if they could keep participation high, or even steady, throughout the three and a half month slowdown. The numbers aren't final yet, but the preliminary data looks very promising.

The Quiet Sound team expects to receive the final report from their marine mammal consultants in June, including an acoustic analysis. At that point, they’ll learn if they met or exceeded the 45% reduction in sound intensity that made the trial so promising.

Quiet Sound is also taking steps towards a second slowdown area. They are studying potential geographic areas, prioritizing where large commercial vessel traffic overlaps with SRKW foraging areas.

The process also entails applying for more funding and working with partners from the maritime industry, government, federal agencies and local tribes.

Arnoson also said, personally speaking, she wanted to get out and see the whales from shore. Hopefully, she’s made that happen.