These early stage maritime businesses are meeting the moment

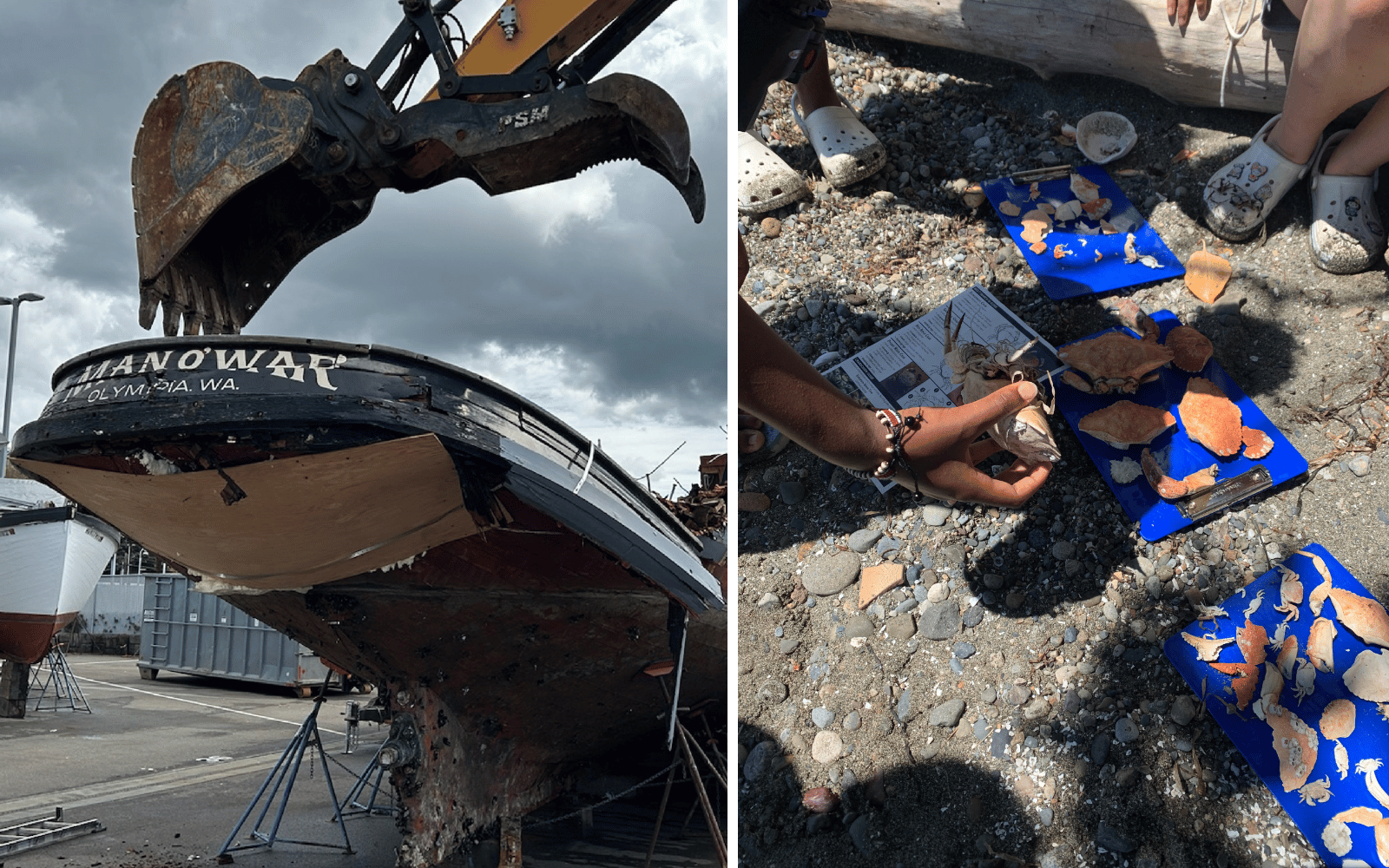

Ebony Welborn of Sea Potential and Frank Gonzales of Gonzo Boat Recycling are maritime problem solvers.

In an industry with century-old shipyards and deep expertise, newer maritime business owners offer a unique perspective. They observed a problem or need, and created a new solution that they believe — supported by their own expertise and conviction — will meet the moment.

Ebony Welborn and Frank Gonzales both started their businesses within the past five years (same as Future Tides) and they’ve taken the plunge, shaping the industry’s future in ways big and small.

At the Seattle Boat Show in February, the two entrepreneurs spoke with Future Tides about what they’ve started, and where they’re heading.

Sea Potential recently expanded its mission to focus on bridging generations in order to expand ocean justice in the community. Currently serving King and Pierce Counties, Sea Potential aspires to expand and become a national, or international, organization.

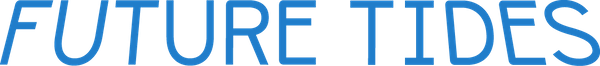

Serving the Pacific Northwest, Gonzo Boats saves the boats they can, has an expanding store of reclaimed materials, and is keeping as much material out of landfills as possible. They are currently hiring.

What they do in their own words

“Our big thing is giving people an option for their end of life boat so they have a way to dispose of it and properly, and that it's actually being recycled instead of going into the landfill.” - Frank Gonzales

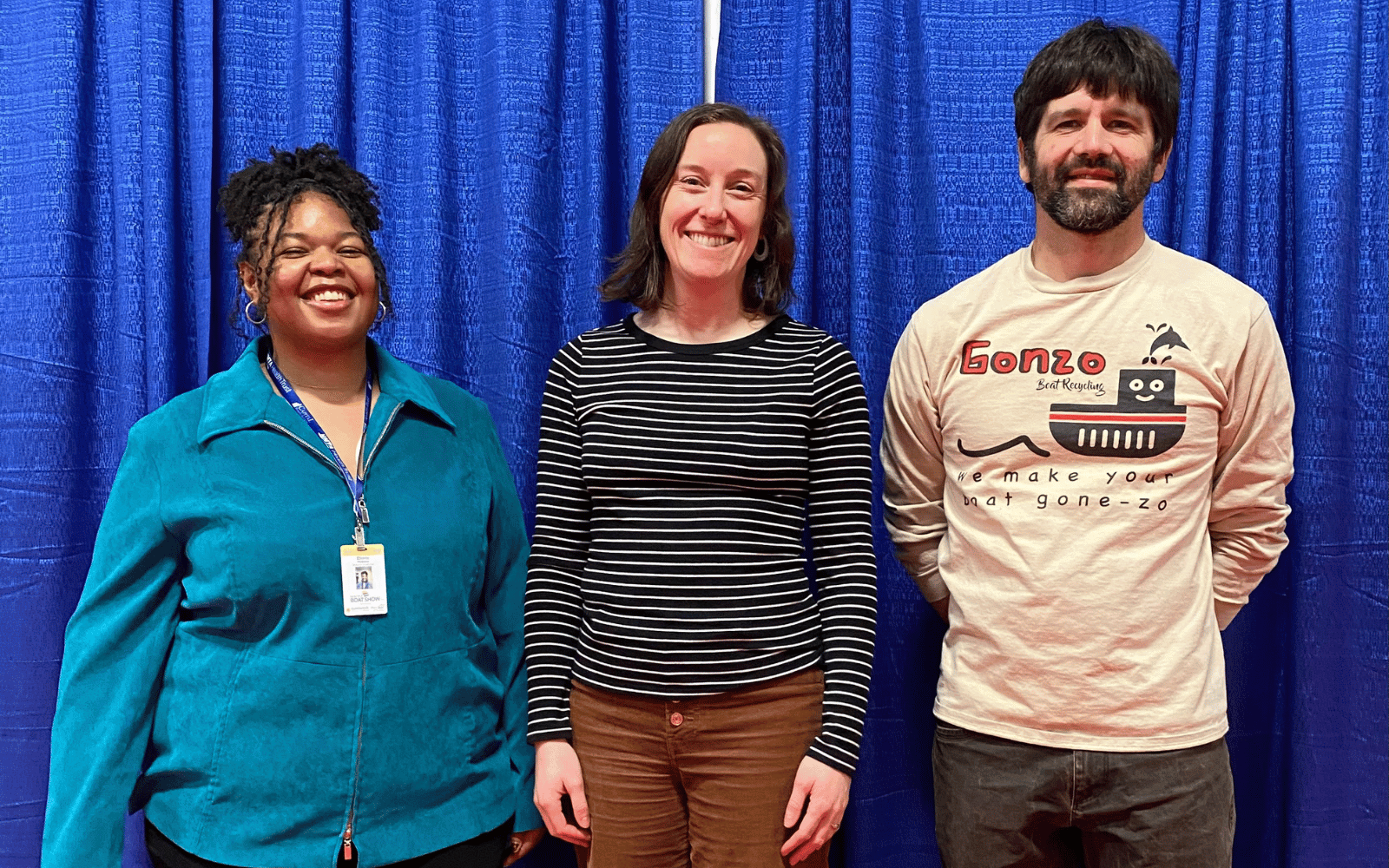

“Part of our work is doing youth engagement...helping youth process any generational or individual trauma they could have around water, really helping them build a heart-based connection to land and water, and then introduce them to career tasks available to them. And the other side of our organization works with industry on their workplace culture to make sure the folks that they're trying to bring into industry feel supported and seen, and contribute to the innovation within maritime.” - Ebony Welborn

Multifaceted businesses

With their background in marine science, youth work was an easy connection for the Sea Potential co-founders.

While doing market research for their budding venture, they identified a need for the maritime industry as well. As a result, they created a consulting arm to help employers create a workplace culture that the BIPOC community can really invest in. To date, they've worked with organizations such as Maritime High School, Environmental Science Center and Washington Sea Grant.

When Gonzales started his business, he expected to largely be working with the state and public entities, which have been increasingly tasked with identifying and removing derelict or abandoned vessels that may become an environmental hazard.

He didn’t expect how much the recycling side of the business would grow though. He's learned that many private individuals are seeking a responsible way to dispose of their boat, and are willing to hire a service. Gonzales said this unexpected demand helped the recycling side of the business grow much faster.

How to grow

Both companies are experiencing growth and using the experiences of the past few years to figure out where to go next.

“We're hitting a growth point where it's like, ‘it's going to have to grow bigger than me,’ and we're working on bringing in employees and learning that whole part,” Gonzales said.

The question of “what’s next?” kept bringing them back to a retail store, where the parts that come off boats are available for sale to the public.

“We've been working on remodeling a historic farm that's over 100 years old, and it's right next to the highway in Arlington, and is going to be very accessible,” Gonzales said.

The age and condition of the farm created more challenges than he’d hoped, but Gonzales said the future store is gradually coming together. The physical storefront will be a key part of the recycling system Gonzo Boats is building out.

“It doesn't do much good if we just take the parts off the boat and then set them on a shelf that nobody can get to,” he explained.

Gonzo Boat’s booth at the Boat Show offered a preview of this future retail space. Tables sat covered with winches, cleats, ship’s wheels, dining sets and more. A pre-1960 Skagit Plastics 17-foot runabout sat in the back with a large “Adopt Me” banner — another facet of Gonzo Boats’ efforts to keep material out of landfills, by trying to give deserving boats a second chance.

For Sea Potential, the path forward surfaced via their extensive partnerships with schools, maritime employers, and community organizations.

They learned that when it comes to getting a job in the maritime industry, a lot of recruiting is based on in-person meetings or established connections through family and friends. This same industry is stepping up its recruitment efforts, to adapt to a changing region and declining workforce.

At the same time, they began to hear from past youth program participants, looking for help connecting with a career.

Through a deep listening process, Sea Potential began to see a way to bridge this well-known gap. It also creates a bridge between their youth programs and workplace consulting.

Their solution? Reimagining the “job board” to create a more centralized place for industry opportunities, and help employers recruit and retain through a certification process.

“We decided to let our community know we feel really good about them, we have a relationship with them and we trust them with your talent,” Welborn said of the certification process.

Dialing in a business model

A big part of business, and staying in business, is a revenue model. Future Tides asked about the basics of each business’ model and how they plan to stay funded going forward.

Gonzo Boats works with both private boat owners, state agencies and private marinas for the removal, recycling and disposal of boats. Gonzales said each of these different customers have their own spending cycles. In order to support his expanding business and employees, he needs to fill in some of the gaps, and hopes the retail store will help with that.

“People work on their boats at different times than when they get rid of their boats, as it turns out,” Gonzales said.

Sea Potential is a slightly different model, but also utilizes different revenue sources to fill in the gaps. They are organized as an LLC with a fiscal sponsor, so they can receive grants much like a nonprofit would. Welborn said this funds the youth programming.

Meanwhile, their consulting service, which includes environmental education and workplace culture consulting, is their “for profit” work that brings in revenue. Welborn said this fits because of their many partnerships and focus on relationships.

Their next revenue stream will be the new job board, with its paid certification feature. This is a new model for Sea Potential, expanding from the hands-on nature of youth programming, and the one-on-one work of consulting.

“We're hoping that brings in more money without us having to do, necessarily, the work wholeheartedly, because our work is so relationship-based and we have to be in person,” Welborn explained.

They are also reaching that phase of entrepreneurship where, like Gonzales said, “it's going to have to grow bigger than me.”

Before they took the plunge

Growing up in small rural communities in North and South Carolina, Welborn spent a lot of time outdoors.

“That was kind of the only thing to do out there, and that's kind of how I ended up building my relationship to land and water,” she said.

In college, she realized she wanted a career that protected the land and the water. A series of internships took her to Florida and then, fatefully, to Washington state. Through the EarthCorps program, she met her co-founder Savannah Smith who grew up in Washington and worked in the marine science space.

One day, they were asked: If you could do anything in the world, what would it be if money wasn't a problem?

They had the same answer: We want to connect BIPOC youth to marine science and help them have an easier time with that. The 2020 Black Lives Matter movement further fueled their desire to pursue this idea, and their internship program created the space for them to do that.

It happened quickly, and almost unexpectedly. They landed their first investor and had three months to turn their vision into the first phase of Sea Potential.

“A lot of our community is very excited to have opportunities around maritime experiences, which is success for us, that there is an interest and people want to be doing that.” - Ebony Welborn

Gonzales’ journey took a turn thanks to Seattle traffic. He grew up in Arlington, Washington, where his business is now based and primarily spent time on ski boats or camping.

He lived on a boat while studying at the University of Washington, got a degree in computer engineering and worked at Microsoft. Some software engineers would’ve simply bought a boat and stopped there.

“I would sit at my desk at Microsoft browsing the internet instead of sitting in traffic,” Gonzales said.

“And I was browsing for old boats and boat parts and Craigslist and all of that. And I kept buying old boats and working on them. And eventually it's like, ‘man, I wonder if I can make my hobby my job and still enjoy it?”

He went on to work as a Ride the Ducks captain, a shipwright, a marina manager, and for the Northwest Marine Trade Association (which organizes the Seattle Boat Show). In those last two positions, Gonzales said he sat in many meetings where people complained about the issue of derelict boats. He heard again and again, “there’s a big problem and all we need is money, and there’s no solution.”

“After a while, it's like, well, both old boats are my passion, and yes, I think there is a solution. I'll make it for you. Here’s the solution,” Gonzales said.

Meeting the moment and what's next

“I feel like I actually really hit the right time in terms of starting it," Gonzales said.

"That there is some public funding available, that we're able to actually make progress, that people are aware enough of the issue that they actually want to do the right thing.”

But that awareness is not universal, even in the Pacific Northwest. Gonzo Boats is working towards opening a location in the Vancouver-Portland area and Gonzales said the awareness and the funding is different there.

They currently recycle or salvage 50% of the vessels by weight. He wants to take that further.

“Where can we set money aside so that we can invest in better forms of recycling and fiberglass, for example, and improving the process so that this becomes a better thing and stays sustainable,” he said.

With Sea Potential, Welborn said they are meeting the moment by addressing the issue of expanding and diversifying the maritime workforce. It’s a chance to not only support the current industry, but also maritime innovation, as more people get involved and bring their creative minds.

“We're excited to see in the future how the industry is more diverse, how the innovation grows over time,” Welborn said.

She also pointed out that outside of Washington, the maritime industry is already very diverse.

“Bringing that same diversity that’s in global maritime culture into Washington would be really cool to see what happens,” she said.

How they view our modern maritime community

Both maritime problem solvers see the strength, and challenges of the region’s maritime industry and community.

“One of the things about the boating community, it makes the big world small, and so that's been a very important part and helped me as I grew it from a hobby to a career,” Gonzales said. “And I think we have a lot of problems also in our maritime industry.”

He identified two major issues in particular. The first, is the cost of everything from moorage to boats can make boating less affordable, or even out of reach, for people. Second is the derelict vessel issue, where abandoned or neglected boats take up limited moorage space and threaten to pollute the waterways.

“My little part to play in that, is giving an option for those boats, giving us an outlet for that,” Gonzales said. “Then with our retail of used parts, hopefully help keep the cost down.”

But, he added that “some people have to go buy the new stuff so there is used stuff for the people who, that's not in the cards for them, can still stay in boating with what we have to offer.”

“It was one of the most challenging projects we've worked on, but it was also one of the most rewarding, in that it provided so much back instead of just bringing in a construction company and crunching it up.” - Frank Gonzales

Welborn defined the region’s maritime community in one word: family.

“Being focused on building relationships with all these different maritime communities is just a family at this point,” she said. “Understanding just all the different moving components, whether that be recreation, education, career, I've just been enjoying learning. And I think maritime is about learning and evolving and connecting in general.”

Some of the challenges she sees also relate back to Sea Potential’s mission, and the need to support communities of color, making maritime more accessible through experience and knowledge.

Welborn said the challenge is making people aware about the career paths and opportunities available to them, along with expenses that might exclude some communities. Plus, the maritime’s aging workforce is a well documented and often discussed problem.

“That's the challenge that we're trying to address by introducing our communities and allowing them to be a part of the career options available to them,” Welborn said. “We feel like that could be a solution on the other side of it.”